A Tale of Twin Cities: Nature's Starring Role in the Founding of Minneapolis and St. Paul

By: Bill Walker

April 03, 2019

Category: History

We humans like to think we’re in charge. That somehow, thanks to our superior intellect (or at least our opposable thumbs), we have become “the boss” over nature. Yet, all it takes is one good Minnesota spring thaw to remind us who’s really in charge.

I’ve been giving this a lot of thought recently – mainly while pumping water out of my basement. Minnesota’s “instant spring” temperatures have caused flooding throughout the state, swelling the three rivers that give the Park District its name — the Mississippi, Minnesota and Crow.

In our insulated, climate-controlled modern world, we don’t often think about how intertwined we are with nature. That is, until the water starts to rise.

But nature – whether we realize it or not – has always played a starring role in the human drama. Throughout time and across cultures, nature has provided the raw materials upon which human history is built. Where we live, what we eat, how we connect to other people – all these things and more are influenced, if not driven, by the many resources nature provides us and how we choose to use them.

Take for example, the history of our own Twin Cities. In many ways, nothing seems further from the idea of “nature” than an urban-built environment.

But did you know that “nature” is at the very heart of the story of how the Twin Cities came to be? It’s true! Thousands of years ago, Mother Nature put in motion a series of events that would set the stage for the eventual founding of not one, but two distinct urban centers right here on the banks of the Upper Mississippi.

And like this year’s spring floods, it all started with an extreme buildup of snow and ice.

The Amazing Wandering Waterfall

About 12,000 years ago, our region (and most of the northern U.S. and Canada for that matter) was covered by a thick blanket of snow and ice.

Then suddenly (like this spring) it got warmer. Water surging from a huge lake born of the swiftly melting glaciers formed great rivers that cut across the land. This flow created what we know today as the Minnesota, and to a lesser extent, Mississippi River valleys.

Just below where the two rivers converged, a huge waterfall formed. Taller than modern-day Niagara Falls, the waterfall once stood about where the “High Bridge” now crosses the Mississippi River near downtown St. Paul.

The geology of this ancient waterfall was unique. Above the falls, a thick layer of hard limestone sat atop a much softer layer of sandstone rock.

As the raging floodwaters poured over the limestone edge of the falls, the churning waters ate away at the soft sandstone underneath (sandstone is so soft that you can scratch it with your fingernail).

Eventually, the churning waters would eat away enough of the sandstone foundation to undermine the limestone above. When this happened, the limestone would break off under the weight of the rushing water, sending huge pieces of jagged rock crumbling over the falls into the riverbed below.

In this manner, over thousands of years and countless erosion cycles, the waterfall receded over ten miles upstream. You can see evidence of its retreat today in the steep terraces of Mississippi Gorge Regional Park (managed by the Minneapolis Park Board) or the tall sandstone bluffs along Shepherd Road as you approach downtown St. Paul from the west.

In a Land, Down by the River

By the 1600s, what remained of the once mighty waterfall was located in the heart of what is now downtown Minneapolis.

The Dakota people living nearby called the falls “Owámniyomni” in reference to their turbulent waters (Source: Open Rivers Journal). The Dakota were drawn to the region by the natural resources that the area around the falls provided.

They harvested the river valley’s vast supplies of fish and game, and planted corn, beans and other crops in the rich soils of the floodplain. They hunted bison seasonally on the prairies to the west, boiled maple sap into sugar in the nearby Big Woods, and used the rivers to travel and trade with other indigenous communities further afield.

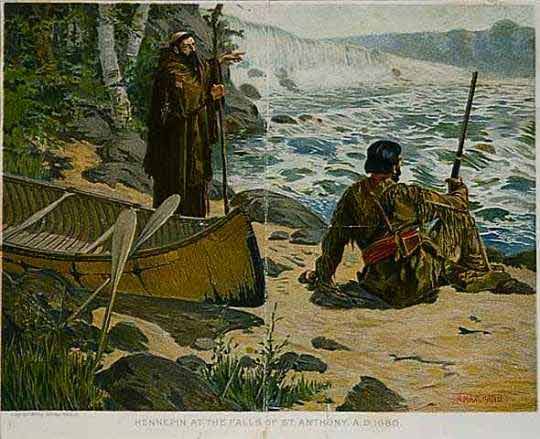

Then, in 1680, Father Louis Hennepin, traveling with a small group of Dakota people through the region, became the first European to see the falls

Image courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society.

Taken by their beauty, he renamed them St. Anthony Falls in honor of his patron saint, Saint Anthony of Padua. Subsequent years of Euro-American exploration and colonization made this the name we are most familiar with today (Source: National Park Service).

A New Look at an Old Waterfall

Between 1680 and 1800, Euro-American travelers described many of the same natural resources that had drawn the Dakota people to the region generations earlier. However, the cultural lens through which they viewed nature’s bounty led them to different conclusions about what to make of those resources.

Like the Dakota, early French-Canadian, and later English explorers saw the region’s rivers as highways that led to areas of rich game. However, while the Dakota harvested a wide variety of animals for subsistence, Euro-Americans were almost exclusively interested in a small number of fur-bearing animals for trade.

The agricultural potential of the river valleys was also noted by early Euro-American visitors, though their agricultural practices varied greatly from those of the Dakota people.

But the real diversion in how the region’s natural resources were viewed – the diversion that led the way to today’s Twin Cities – came in the late 1820s.

The Hum of Industry

Today, when most Americans stop to look at a waterfall, they do so to admire its beauty. To be sure, Euro-Americans of the early 1800s were impressed with the natural beauty of St Anthony Falls. Landscape artists came in droves, painting the only images we now have of the falls in their natural state.

But beyond beauty, Euro-Americans of this era saw something else – something that would result in the eventual destruction of the natural falls. When they looked at the falls, they saw dollar signs!

By the late 1820s, the Industrial Revolution was in full swing. Throughout Europe and the northeastern U.S., factories were cropping up along riverbanks everywhere, converting the potential energy of falling water into the mechanical muscle then driving the newly industrialized economy.

When “enterprising” individuals of this era looked at St. Anthony Falls, they could hardly believe their luck. It was the only natural falls along the entire length of the Mississippi – a river that was becoming increasingly important to the westwardly expanding nation.

All one had to do was acquire the land on either side of the falls, and the rights to all that water power would be theirs. Factories could be built, and the money would start rolling in.

However, the natural course of the Mississippi River, which follows a sideways “S” curve as it travels downstream of the falls, was another key factor.

Early steamboat captains quickly learned that the stretch of river between St. Anthony Falls and its confluence with the Minnesota (at Mendota) was not reliably navigable by large steamboats.

This was in part because of the rocky debris left behind by the eroding falls, and the speed of the river as it passed through the gorge. At first glance, this might have hampered the industrial promise of the falls, since anything manufactured there could not be easily shipped downstream by boat.

But because of the natural “S” curve in the river’s course, manufactured goods from St. Anthony Falls could be transported a short distance overland – roughly 8 miles to the east – along a road that would reconnect with the river downstream of the gorge, just below the site of the ancient waterfall.

Here the river was slow and deep, and large riverboats could be easily docked along its banks, ready to receive their cargo. From this point – the “navigational head” of the Mississippi River – manufactured goods could be easily transported by water to almost any port in the world touched by American ships.

From an industrialist’s point-of-view, nature had set the stage perfectly for the development of two “twin cities.” An industrial city of factories and mills would be built around St. Anthony Falls, and a port city of warehouses and levees would be built at the Mississippi River’s head of navigation. Between 1840 and 1860, that’s pretty much what happened.

St. Paul was settled first, shortly after an 1837 treaty with the Dakota people opened the land for non-Indian settlement. Its place at the navigational head of the Mississippi River made St. Paul the natural port-of-entry for new immigrants and industry streaming into the region from points south along the Mississippi. In 1849, the booming city was named capital of the newly formed Minnesota Territory, and has remained Minnesota’s capital ever since.

In 1838, Franklin Steele and Pierre Bottineau claimed land on the east side of the falls, naming the new settlement St. Anthony.

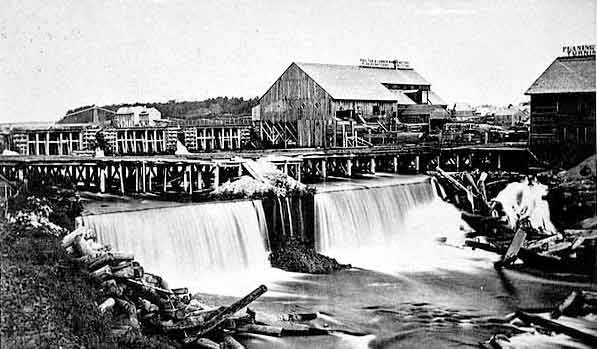

Ten years later, in 1848, the first lumber commercially milled at St. Anthony Falls was rolling out of Steele’s mill.

In 1851, additional treaties with the Dakota were signed, opening the west bank of the river for additional settlement and commercial development. A new city, named Minneapolis, was established on the west bank. As business boomed, Minneapolis grew, eventually absorbing St. Anthony in 1872.

Lumber mills dominated the industrial produce of the falls during the early years, though flour mills would eventually become king. Between 1880 and 1930, Minneapolis was widely known as the “flour milling capital of the world,” earning it the nickname, the “Mill City.” All because of humble St. Anthony Falls.

Human Impact on the Natural World

Unfortunately, all this success came at a price. Whether it’s the harnessing of a waterfall in the 1800s, or the harvesting and burning of fossil fuels today, human use of nature’s resources often takes an unexpected toll on nature itself. By the late 1860s, the industrial development of St. Anthony Falls nearly led to their complete collapse.

Remember how the unique geology of the falls caused it to erode and retreat upstream over thousands of years? Well, human development at the falls – in the form of dams, tunnels, millraces and the like – inadvertently sped the erosion of the falls’ sandstone foundation.

In 1869, a tunnel being built under Nicollet Island, just upstream of the falls, collapsed. As water rushed through the collapsed tunnel, it formed whirlpools that caused large sections of the natural falls to collapse. Left unchecked, the rushing waters would have led to the total destruction of the falls, ending Minneapolis’ dreams of milling greatness.

To save the city, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was called in to “save” the falls (Source: National Center for Earth-surface Dynamics). A concrete dike was built under the river, replacing the natural waterfall. The dike was topped by a wooden apron (and more recently, a concrete spillway) to smooth the flow of water over the edge (Source: Minnesota Historical Society). This action allowed the mills to remain, but the natural falls were lost forever.

Back to Nature

By the 1930s, Minneapolis milling was on the decline. Newer technology and other human factors made the milling industry less reliant on the waterpower of St. Anthony Falls, and businesses moved elsewhere. As factories closed, and buildings went vacant, the Twin Cities – at least for a time – turned their backs on the river that had given them life.

But in recent years, the river – and the falls – have been experiencing a rebirth.

Once vacant warehouses are now chic apartments and condominiums. Parks dot the once industrial landscape, including two managed by Three Rivers (Mississippi Gateway and North Mississippi regional parks).

As our modern eyes once again reassess the natural resources of the area, watch for new “give and take” cycles to emerge between humans and the natural world.

But in the weeks ahead, as news reports anxiously talk of rising floodwaters and strained riverbanks, don’t forget to acknowledge who’s really in charge!

About the Author

Bill Walker is the Cultural Resources Program Manager at Three Rivers. He has been with Three Rivers for 10 years and has more than 20 years of experience in the field of cultural history, including working for the National Park Service and a variety of local historical societies and museums. Bill loves that all 27,000 + acres of Three Rivers parklands have a human story to tell – some reaching back over 10,000 years! Knowing the stories of how people have connected with the land in the past helps us construct a sense of place for enjoying these spaces today.

Related Blog Posts

Nature's Classroom for 50 Years: The Dream of Lowry Nature Center

By: Allison Neaton

Lowry Nature Center turns 50 years old in 2019. Discover how the dream of one man became a reality and how Goodrich Lowry helped shape the future of what is now Three Rivers Park District.

Have you ever wondered why we “deck the halls with boughs of holly” each December or why we light Hanukkah menorahs on midwinter nights? Read on for more about the unknown stories and history behind some of our holiday traditions.

A Grimm Dairy Tale

By: Bill Walker

Did you know that we wouldn't have locally made ice cream, butter, cheese curds and other dairy products if it wasn't for one determined farmer who settled in Carver County in the 1800s? Read on to learn about Minnesota's great dairy tale; alfalfa will never look the same.