Have you ever thought about how we kept food and drink cold and preserved before we had electric refrigerators in our homes? Well, harvested ice was the answer.

Thankfully Minnesota and all the other northern tier states were very fortunate to have many lakes and rivers and very cold winters, which meant a near endless supply of ice for harvesting.

Ice harvesting was a very large industry in America for about 150 years, from the early 1800s to the mid-1950s. It was called harvesting because it involved the gathering of a cold-weather “crop.”

How Ice Is Harvested

In early winter, ice blocks were cut from frozen lakes and rivers. The blocks usually had a thickness of 16-18 inches and were 22 inches square. Each block weighed about 250-300 pounds.

To begin the process, a horse-drawn plow would cut a grid on the lake surface that defined each block to be harvested. Men would finalize the individual blocks by using breaker bars and large five-foot hand saws, but by the 1920s, circular blades on gas engines replaced the horses and plows.

The blocks were floated to the shoreline where they were stored in insulated buildings called ice houses. Sawdust or straw was used to insulate the houses, depending on what was most available locally.

These houses ranged from maybe 10-30 tons in small communities and farms to 200,000-300,000 tons in bigger cities.

The harvests usually ran 24 hours per day! Imagine working the night shift on a cold winter night with only the moonlight and kerosene lanterns for illumination, all the while being near open water where the ice had been cut out.

Ice Deliveries

In spring, summer and fall, ice was delivered to homes, businesses and railroads for preserving food. Early delivery was by horse-drawn wagons and by the 1920s, ice was delivered by truck.

Depending on the outdoor temperatures, the quality of insulation in the ice house and how many times the door of the icebox was opened, a home icebox may have needed re-icing a couple times a week, especially during the hot summer months. With no central air conditioning then, kitchen temperatures were often higher than the outside temperatures.

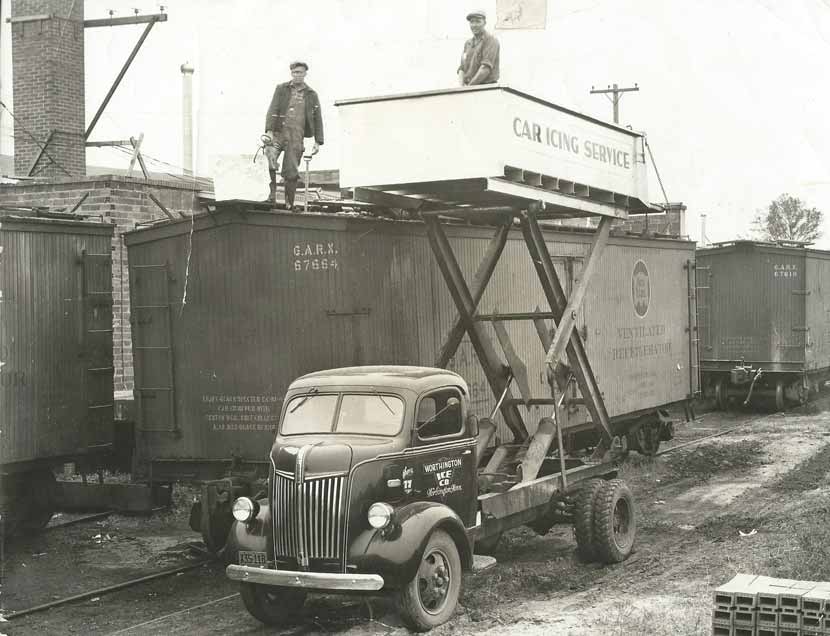

Cross-country railroad shipments of meat and produce may have needed to be re-iced every 200-300 miles along their summer routes.

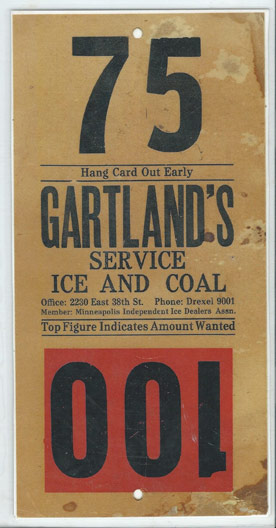

To order more ice, customers would put a numbered card in the porch window to indicate how many pounds of ice were needed on delivery day. The delivery man would cut the block to the required size and deliver it into the icebox.

The cost was 25 cents per 100 pounds in the 1930s. But remember, wages were maybe 25-30 cents per hour.

Image courtesy of Tim Graf.

How the Ice Industry Began

The ice harvest industry got its start in New England in the early 1800s. One businessman by the name of Frederick Tudor shipped ice around the world and as far away as Bombay, India.

By the late 1880s, ice was the second largest export in the United States, behind cotton. By 1886, 25 million tons were cut and stored or shipped in the U.S. To put things into perspective, one acre of ice at over 12-inches thick would yield about 1,000 tons — a football field is just over one acre in area.

However, by this time, technology allowed for mechanical refrigeration equipment to make ice in warm climates. This caused world and southern markets for ice to go away, but interestingly enough, the home, business and railroad markets were growing at this time and the ice industry got a second life.

At the same time, only 6.4 million tons of iron and 2.9 million tons of steel were produced per year. In 1900, ice harvesting was the 9th largest industry in the United States, in financial terms.

In 1914, the U.S. used 24 million tons of manufactured ice and 26 million tons of natural ice. By 1932, there were 30 million family households in America and still one-third of the population had no refrigerator or icebox.

In the late 1930s, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order to create the Rural Electrification Administration, which brought electricity to rural Minnesota, and of course, the option for mechanical refrigeration.

By 1950, 90% of American city homes had mechanical refrigerators and 80% of the rural households were so equipped.

This marked the second time the industry faded. Ice demand declined through the World War II years. By the mid 1950s, the ice business was almost gone.

It had survived for well over a hundred years due to many innovations in tools and processes and technology, but it could not compete with electricity and could not support the rapidly growing demand for cold.

Ice Harvesting Today

The railroads used ice into the late 1960s and some remote northern resorts still do a small harvest today. In Minnesota, we have had the opportunity to see the process on a few occasions when ice was being cut for St. Paul ice palaces.

My Connection to the Ice Harvest

My grandparents operated the Worthington Ice Company in southwest Minnesota through the 1930s. They harvested up to 40,000 tons of ice each winter. One-fourth of the ice was stored locally and two-thirds was sold to the railroad for re-icing refrigerated cars that hauled meat, poultry and vegetables across America.

In an effort to keep the history of the industry alive, we started the ice harvest programs and events at Richardson Nature Center.

Three Rivers and Ice Harvesting

Ice harvesting has grown and evolved over the last 20 years at Three Rivers. There is school programming where about 200 fourth- and fifth-graders learn about ice harvesting as well as a public Ice Harvesting Day event that has drawn up to 500 people!

It is a hands-on event where everyone has the opportunity to use authentic tools to experience a bygone essential part of American history. I’ve found kids learn quickly that one stays warmer operating the big hand saw than they do standing on the ice watching someone else do it.

We now seldom exceed 12 inches on the Richardson ponds for the event in the last week of January, and in the past few years, we have experienced near 40-degree temperatures on event days.

Want to learn how to harvest ice yourself? Come to Climate Conversations: Ice Harvest 2020 at Richardson Nature Center on January 25 and experience the adventures of ice harvesting!

About the Author

Tim Graf is a Burnsville resident who grew up in Worthington, Minnesota. There, he heard many stories of the ice business from his grandma and dad. He started recording the stories, researched more about the business and collected tools and artifacts. In 1998, he attended a Hyland Winter Fest event that advertised ice harvesting where he found one lonely ice saw in a hole at the edge of the activity area. He met park employee, Tim Anderson, and offered to help expand the display for the winter of 1999. He is now a 20-year volunteer with Three Rivers. Tim also taught ice harvesting to thousands of school kids at the Bloomington River Rendezvous and he is currently writing a local history of the ice business in Worthington.

Related Blog Posts

Sustainability Thread: Climate Conversations

By: Rachel Van Vlaenderen

With more than 27,000 acres of land, visitors and staff see changes every day in our parks and on our trails. Much of what our staff has noticed has been a transformation in our weather and climate. Join the conversation.

Hard Cider: A Story of War, Immigration and Prohibition

By: Brandon Baker

Making apple cider is an annual tradition at Eastman Nature Center, and it is a tradition that goes back thousands of years. Even though hard cider was the drink of choice early in American history, people hardly drink apple cider today, and hard cider is only recently making a resurgence. Why did cider disappear, and how did this affect our parks?

A Grimm Dairy Tale

By: Bill Walker

Did you know that we wouldn't have locally made ice cream, butter, cheese curds and other dairy products if it wasn't for one determined farmer who settled in Carver County in the 1800s? Read on to learn about Minnesota's great dairy tale; alfalfa will never look the same.