Osprey Reintroduction: The Great Success Story

By: Steven Hogg

May 20, 2019

Category: Resource Management

I remember the first time I watched an osprey dive and catch a fish — what a thrill! The speed it hit the water was intense. Perfectly-designed wings reached way up and bent at the wrist to pick itself and the fish out of the water. Talons and little scales gripped the fish, positioning it head first to allow better aerodynamics in flight.

“What an amazing bird!” is all that came to my mind.

Today, I am lucky to work with these beautiful birds as a part of my job. When I think back, it wasn’t that long ago when ospreys were not found in this area.

WHAT HAPPENED TO THE OSPREYS?

Ospreys used to be very common in southern Minnesota. They disappeared in the Twin Cities area after World World II, though, due to habitat loss, human persecution and the use of DDT pesticides.

In 1984, Three Rivers Park District began a restoration effort to bring ospreys back. Six young birds were collected from nests in northern Minnesota that first year and brought to Carver Park Reserve.

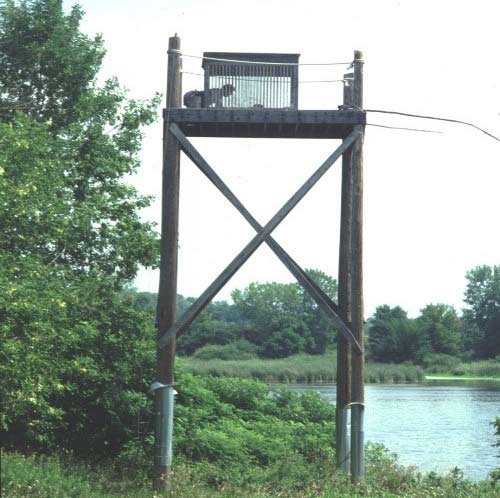

Young birds were raised in what biologists call hack boxes. Hack boxes are cages placed high on telephone poles to mimic a nest. These cages keep the chicks protected from the sun and predators and allowed daily feedings by staff or volunteers.

The birds were “released” from the box when they were eight weeks old and soon able to fly.

Then, nature helped make this reintroduction a major success story.

NATURE’S HELP: OSPREY ADAPTATIONS

Once they leave a nest or hack box, ospreys can survive on their own without further help.

- They can teach themselves to hunt their sole food source, fish.

- Because they only eat fish, ospreys cannot stay where there is ice cover. They migrate as far south as South America and can do so using only their instincts (versus needing to follow their parents or other adult birds).

- Young birds stay south until they are sexually mature at about two or three years old. When the adults return north to nest, the males typically find their way back to where they fledged (or learned how to fly), while the females tend to spread out a bit farther.

- Ospreys generally mate for life. Once a nest is successful, the pair returns to the same nest year after year. (It should be noted that the first year may not be successful: It takes a lot of time to find a mate, build the nest, and raise chicks before needing to head south in September!)

- Wild ospreys can live up to 20 to 25 years, and each year they raise 1-3 chicks. A single pair of birds can raise several dozens of chicks in a lifetime.

PROVIDING NESTING OPTIONS

Ospreys historically nested in dead trees above the forest canopy because of great-horned owls, which ambush ospreys at night.

To promote nesting in the Twin Cities area, nest platforms were placed in open spaces within our parks and elsewhere through partnerships from 1984-1995.

The ospreys used these platforms, but they also eventually took advantage of non-natural structures such as water towers, cell phone towers, bridges, and field/stadium light poles.

Because there were plentiful nesting options and food sources near where they fledged, returning adult ospreys (and their many descendants) stayed local, which greatly helped increase their population in the Twin Cities.

TRACKING OSPREYS: BANDING

Historically, every chick possible was banded each year. This helped determine the success of the reintroduction program and allowed us to monitor individual birds to learn as much as we could about the species.

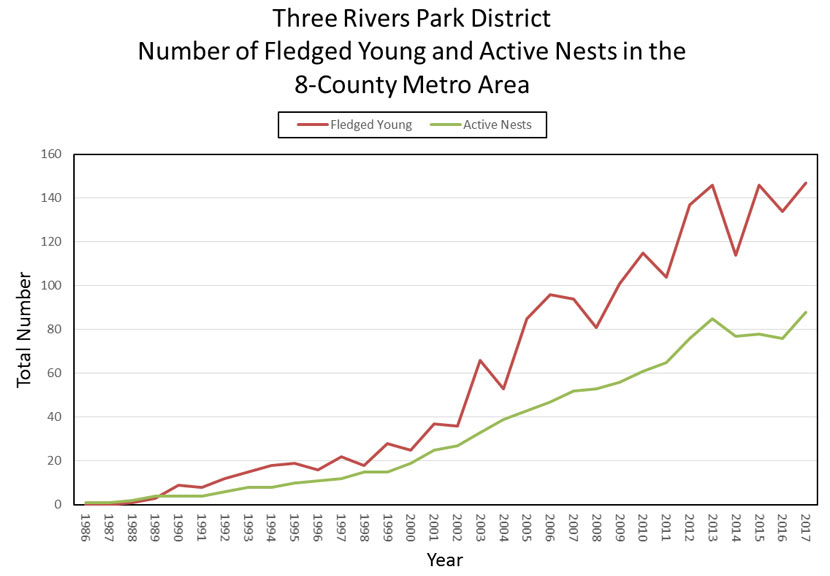

Within the last 10 years, there has been a steady increase in population, and it is no longer possible to annually band all 140+ chicks. (We are constantly thinking about the birds and their welfare, however, and would gladly assist in banding for a research project if needed.)

Today, osprey banding is mostly done at our nature centers to monitor a small subset of birds and to share their story during scheduled programs. It is always great to see participants’ eyes light up when they see a baby osprey!

TRACKING OSPREYS: CITIZEN SCIENCE MONITORING

We know of 148 osprey nest sites today, with 90 occupied each summer, and we couldn't monitor all of these locations without citizen science volunteers. Currently, 32 volunteers travel around the Twin Cities a few times each year to monitor these known nest locations using binoculars and spotting scopes. These volunteers provide valuable information and observations to track nest successes, nest failures, and total chicks each season.

During the first 11 years of the reintroduction effort, 144 young ospreys were brought from northern Minnesota and released in the eight-county metropolitan area. In 2018 alone, 137 chicks hatched in this area.

The osprey is a bird that has been able to adapt to a growing metropolitan area through initial reintroduction efforts and the ban of DDT. Their story has showcased how wildlife can survive in an urban area when given the right tools for success.

About the Author

Steven Hogg is the Wildlife Supervisor at Three Rivers Park District and has been working for the Park District for 13 years. After graduating from the University of Alberta with a degree in Environmental and Conservation Biology, he moved to Minnesota to marry his beautiful Minnesota bride. Steven has always had a passion and dedication for wildlife, even when he was young. This passion is what lead him into a career where he strives for the proper orchestration of research, management, and politics to ensure natural resources and wildlife are given a voice. In his spare time, which there is little of with his three kids, Steven likes to farm, hunt, and fish.

Related Blog Posts

9 Things We Learned from the Medicine Lake Urban Turtle Project

By: John Moriarty

Where do spiny softshell turtles go after nesting on the beach at French Regional Park? How far do softshell, painted and snapping turtles travel in the water? Are they active in winter or affected by water quality? Find out what we learned during the Medicine Lake urban turtle project.

Reintroducing Wildlife at Three Rivers

By: John Moriarty

What do trumpeter swans, regal fritillary butterflies and bullsnakes have in common? All were reintroduced into Three Rivers parks. Read about what goes into reintroducing a species and discover what others were successfully reintroduced — some might surprise you!

Prairie Burns: Protecting Precious Habitat with Fire

By: Erin Korsmo

Three Rivers conducts controlled burns at its prairies each spring. Learn what goes into burning a prairie and why fire is so important to preserving this special habitat.